As an owner of a print lab we see the most common mistakes people make when submitting their files for printing. Even the most experienced photographer can submit a file that will not yield the best printing results due to a small oversight that can have a large impact the way the print turns out. Below I’ll cover the different elements of where things can go wrong during the file preparation process.

Monitors

What is calibration for?

Ultimately, you want to be able to match your monitor to your print. To do that, you must calibrate your monitor. A calibration adjusts the balance of color coming out of your monitor so that it more accurately reflects what your print will look like. This ensures that modifications you make to your image will be correctly reflected in your final product.

Even with calibration, there will be some variation between monitors and your print. Not every monitor is built the same so not every monitor will appear the same, but the calibration will ensure that this variation is minimal.

How do I calibrate my monitor?

To perform a calibration you need two things: 1) a spectrometer and 2) calibration software. A spectrometer is a piece of hardware that detects the balance of colors coming from your monitor and allows the calibration software to make adjustments to that balance. As the software makes changes to your monitor, the spectrometer detects the actual changes made and allows the software to make further adjustments. This continues until the monitor gets as close as possible to true color, within the limits of your monitor itself.

Note: A poor monitor will NEVER give you an accurate picture, no matter how frequently it is calibrated. Spectrometers can range in price from $60 to $500. You can buy calibration software from companies such as Xrite or Spyder; more companies are listed below.

How often should I calibrate?

As a rule, you should calibrate your monitor once per month. As your computer ages and the hardware degrades, you may need to calibrate your monitor more frequently.

DDC vs. Regular Monitors

Regular Monitors

On a regular monitor, your video card is only showing color in 8 bits. The limitations of this are dynamic range. An 8-bit monitor cannot show you subtle details in shadows, highlights, and gradations of color.

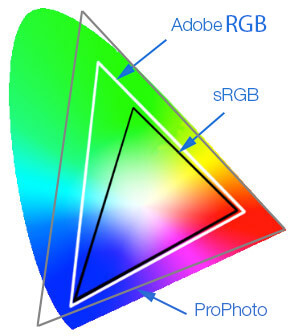

Standard Red Green and Blue (sRGB), which is what regular monitors use, is the color space used most frequently because most devices can show it, making it a safe standard. However, sRGB has one of the smallest dynamic ranges, resulting in poor saturation and gradations like the more advanced monitors have. On regular monitors like these, you cannot accurately set the white point (luminosity), the contrast, or adjust each color channel individually.

DDC Monitors

A DDC monitor can show color in up to 14 bits. These monitors will show 98-108% of Adobe 1998 RGB color space. It has the correct hardware to set the white point correctly as well as the contrast and color channels.

What about ProPhoto?

ProPhoto is a much larger space than any output device can show, whether that’s a monitor or printer. It is a good space to use when editing, but for the purposes of this article and to optimize your print, I recommend editing in Adobe RGB or sRGB.

Most print labs will have you send your file in sRGB to reach the lowest common denominator. Higher-quality labs will recommend Adobe RGB. Most labs can take both. I personally recommend a DDC monitor and Adobe RGB because most high-end printers can print close to that color space, and it will be very close to what you see on your monitor.

CMYK Color mode

Even though a printer may use the CMYK color scheme to print your image, it’s not a good color space to use when editing your image. While it’s true that the sRGB or Adobe RGB colors will be converted when sent to the printer, the printer drivers will typically do this better than the program you are using to edit your images (including Lightroom and Photoshop). To avoid any unneeded loss of information, just leave your image in the color space you edited it in.

Can all monitors be calibrated?

No. Most monitors (including $1500+ models) come out of the box factory-set to make everything look better than life. They appear sharper and the contrast and color saturation is over the top. This will often lead to disappointing results when your print doesn’t look as good as how it does on your screen. It’s like seeing everything through polarized sunglasses, then taking them off and realizing the difference in what you see.

Most monitors lack the hardware to truly recalibrate even with the external hardware/software that you can purchase. Even though you cannot fully calibrate a regular monitor, it’s going to get you a lot closer than if you didn’t do anything.

On a regular monitor, rather than calibrating your monitor, you are calibrating the 8-bit video card. On a DDC monitor, you are calibrating on the LUT table which is 14 bits. Calibrating a DDC monitor gives you a much better calibration and tonal range.

Glossy vs. Matte Screen?

Glossy screens artificially create contrast, saturation, and sharpness. No matter how much you calibrate your monitor, you won’t be able to match a print. You are also fighting the reflection of any light source in your room, which will cause color distortions throughout your image.

A matte screen will give you truer image with 1) no reflection, 2) no inflated saturation and contrast, and 3) a more accurate black and tonal range. Things will look softer on a matte monitor, but that is more accurate to a print.

Color Viewing Conditions

The lighting in your viewing area (house, office, etc.) can also affect the print-to-monitor comparison. The type of lighting in your room has a color ”temperature.” Most of you will be familiar with making sure your image is ”white balanced” in your images. This refers to the spectrum of color that white can appear as, and it’s defined on a Kelvin (K) scale from 1,000K to 10,000K.

Just like having your white balance off in your photo, the light you are using in your viewing area will affect the way white is seen in your print. If you are using fluorescents, your color temperature will be more of a cool blue-green hue (7,000—10,000K). Incandescent bulbs will give off a warmer temperature hue and give your print a yellower tint (1,900—4,000K). The standard color temperature for professional photographers and printers use is 5000K or 6500K.

There are two sources of light to consider when editing images: the light from your monitor and the light in the room you’re working in. For example, most monitors out of the box are considerably brighter than the light in the average viewing room. One of the big selling points of a monitor is how bright it can get. But to do an accurate comparison, you really only need half of the brightness of the average monitor. This “over brightness” is why so many people complain that their prints are darker than their monitor.

Additionally, consider a situation in which your room is fairly dark with incandescent lights (2,000K, very orange) and your monitor is set to twice the brightness and may be set to 9,300K (blue on the scale). The result would show your print as very dark (because of the monitor brightness) and warm (because of the monitor and room color temperature) as compared to the monitor image.

Sometimes people try to lighten the print and add more blue to it to get it to more closely match the screen, but this often leads to a ruined print. Viewed under daylight conditions outside, your print will be way too light and blue. If you look at something in the dark, it will be dark. Calibrating your monitor for your viewing conditions will help you with your brightness differential, but it doesn’t always get you to where you really want to be.

Should I soft proof?

Soft proofing is when you go into software like Photoshop and load a profile to show how the color is going to change based on the particular abilities of the printer you are using. It shows you the limitations of the color and contrast of the device you are printing to and how to edit for that device. If you were to edit the color limitations, it would show you that you are going to lose detail of the image (color detail, shadow, highlights, etc.).

Soft proofing only works on a monitor that you can really calibrate (like a DDC monitor), otherwise, it is not useful. I highly recommend ordering photo proofs (around 8″ x 10″) so you can see firsthand how your file will print and you can compare to your monitor to see where you need to adjust.

File Preparation

Color Space

If you want to be safe but have limited dynamic range, use sRGB, particularly if your monitor is sRGB. You are much more likely to hit your colors on whatever printer you print on. I recommend using Adobe RGB so you can get a little more saturation and dynamic range. Most high-end printers have a color space near Adobe RGB, so you should take advantage of that.

16-bit vs. 8-bit

16-bit is best for editing your images, but it doesn’t make a difference when printing. Since 16-bit printing has been introduced, most printers haven’t been able to hit it at this point. Both Mac OS and Windows drop the bit rate to 8 when sending the file to the printer.

There are a few raster image processors (RIPs) and a few different native drivers from Epson and Cannon can now print 16-bit. But from many test results, they are not providing a noticeable difference on almost any of your images unless you are printing a raw gradient. My recommendation is to edit in 16-bit (in order to have as much flexibility as possible), and when you are done, convert it to an 8-bit file to send to your print lab.

Many print labs cannot truly print in 16-bit, and even a lab which has a 16-bit printer doesn’t realize that their operating system converts it to 8-bit as it sends it to the printer. Saving in 8- bit also makes the file a lot smaller, making the workflow much faster when transferring the file to the print lab. 16-bit files are larger and harder to work with for often unnoticeable improvements to the print.

Color Space (RGB, CMYK, B&W)

As mentioned previously, the majority of labs that are doing high-end printing, whether it be inkjet, dye sublimation, or light jet, work better with an RGB file. The only time you would want to send a CMYK file is if it was going to a printing press or a laser printer.

With greyscale or B&W images, in many cases, it is still better to send it as an RGB file, but you will need to check with your lab. This is because the software used with many printers doesn’t always have a space for greyscale, and you can get a color cast in your printing. Many labs don’t know this and don’t check for it.

File Format

When considering how to save your files, there are two things to take into consideration: size and quality. While a smaller image is easier to send, making it small will result in a loss of data in your image. While losing a little data is often fine, it is important to know what happens when you save a file in order to maintain the quality you want over time.

There are two types of ways to save your image, lossy and lossless. As is sounds, lossless files retain all their data but as a result are often bigger than their lossy counterparts. Common lossless files types include TIFF, LZW, and PNG.

Lossy files result in a loss of information, although often the amount of information lost can be controlled. The most common lossy file type is JPEG. JPEG results in much smaller files, but it does this by finding colors that are close to each other and combining them, for example, three similar shades of grey down to one. While this will not normally result in any noticeable change in the print, it is important not to continually save a JPEG over again since the compression will amplify each time, eventually resulting in an unrecoverable damaged image.

It is worth noting that lossy and lossless are independent of compression. ZIP, LZW, and PNG are lossless but compressed (they only combine identical colors) while JPEG is lossy and compressed (combining similar colors). This is also why you can achieve smaller files with JPEG depending on how similar you chose the colors to be which will be compressed.

Many photographers shoot in RAW, but that is not a file format that you can print. Like TIFF, RAW is simply a package in which all the data for your image is contained. Since the information inside a RAW file differs from camera to camera, there is no universal program which can understand the data in a RAW file. This being said, it has tons of information and is great for editing, but you have to export it into a JPEG or other file format when you are done in order to print the image.

My recommendation in most cases is to send a minimally compressed JPEG. You can adjust that in your software. If the scale is SM-MED-LRG, you want large. If the scale is on a slider, you want 10-12 (Photoshop) or 80%-100% (Lightroom). If you feel like you want the absolute best quality, send a lossless file, but most likely you will not see a difference between a lossless and a minimally compressed JPEG.

Resolution

The best resolution, in most cases, is the resolution which matches the original image. People get into trouble when they start playing with the size because they don’t understand how to use resolution. A printed dot is not the same as a pixel. It might take multiple dots to represent one pixel.

Therefore, needing 300 dpi for whatever size you are printing is a myth. 300 dpi is a catch-all, just like sRGB. It’s the lab trying to tell you that you have enough resolution to print what you want because they assume you don’t understand.

Most printing processes these days can produce beautiful images at 150 dpi or lower. There’s no noticeable difference between 150 and 300 dpi for most images. We have produced beautiful images even as low as 72 dpi. The larger you print your image, the larger your viewing distance is from the image. The average person can’t detect any difference between 72, 150, and 300 at a normal viewing distance. Even up close, an image printed at 150 dpi or even 120 dpi shows no noticeable difference in quality.

Let me illustrate why this can become an issue. Sometimes customers will send us files that are 30”x40” or larger at 300 dpi. Very few cameras (if any) under $40K can take a picture that is this big with this much resolution. In order to get this resolution, most customers would need to “upsample” or add resolution to their image when preparing the file or print. Let’s assume that the original image was 72 dpi. If we assume a 13MP camera, sizing the image to 30”x40” and upsampling to 300 dpi will result in the addition of 400% more pixels to the image!

These are pixels which you have no choice in the position or color. This degrades the image much more than printing at 72 dpi at the same size. You will have a sharper image with more detail that is cleaner overall at a lower resolution than when you attempt to add resolution. Programs like PhotoShop, Lightroom, and other third-party plugins that can add resolution have gotten much better, but most of the time they’re not worth it.

Summary

I recommend saving your files in RBG. Check with your printer for your B&W images to see if they prefer them in RGB as well.

When preparing your file, talk to your printer and see what color space they prefer (Adobe RGB or sRGB). I personally prefer Adobe RGB because it matches the print device much more closely and you can take advantage of the larger color gamut.

Request hard proofs! Many labs will provide low-cost or free proofs when requested. They want your prints to come out accurate just like you do, and print proofs make sure the customer understands how their photo will be printed before committing to a large order.

I recommend converting your image to 8-bit because there won’t be a noticeable difference in 99% of your images, and it speeds up the transfer and processing time.

Send your file at the native resolution that the file was created at. We recommend not removing or adding resolution. Remember it is a myth that you need 300 dpi to get a good image. You will not see any noticeable difference with resolutions as low as 120-150 dpi. Adding resolution degrades the quality and makes your file much larger.

We recommend a JPEG with minimal compression, but if you are concerned about compressing your file, save it .tiff format.

Will Heinitz is the founder and COO of Shiny Prints, a high-end metal print lab that caters to professional artists and photographers. Will works closely with many customers to help bring their images to life and is constantly trying to improve based on the feedback from his customers which is what has developed Shiny Prints to what it is today, and is why it has the reputation of being one of the best metal print labs in the country.